SEARCH THIS SITE:

STONEWORK STYLES:

RESOURCES:

REGIONS:

Click the photo above for a cairn illustration from the 12th Annual Report of the Smithsonian's Bureau of Ethnology; 1891. Another example from the same report is further down this page.

|

Representative early accounts of Native stone cairns in the Northeast

The Memorial History of the City of New York; 1892, James G. Wilson, editor; Vol. 1; Chapter II: The Native Inhabitants of Manhattan and its Indian Antiquities; Edward Mannning Ruttenber; p. 50:

Wa-wa-na-quas-sick is a somewhat lengthy combination, --wa-wa is plural, or many; na signifies good; quas is stone or stones, and ick, place of stones. It all means a pile of memorial stones thrown together to mark a place or event."

Dr. James H. Trumbull, Indian Names of Places, etc., in and on the borders of Connecticut; 1881; p. 53:

Pomperaug: . . . A heap of stones, in the village of Woodbury is supposed to mark the grave of Pomperaug, on which "each member of the tribe, as he passed that way, dropped a small stone, in token of his respect for the fame of the deceased" (Cothren's Woodbury, i. 88). Such memorial stone-heaps were common in New England. From the one in Woodbury both the locality and the mythic sachem probably received their name, which may be interpreted 'place of offering,' or 'contributing.'

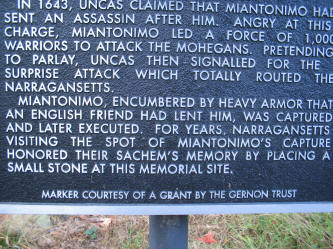

A site in Norwich, CT records a tradition of building stone cairns. It is the Miantonono Monument. The bronze plaque erected by the state tells the story of Miantonomo, a Narragansett sachem who concluded that the various tribes had to form a confederacy to fight the colonists in the wake of the colonists' massacre of the Pequots 1637. His plans were betrayed to the colonists by Uncas, the sachem of his enemies the Mohegans. He and a band of 1000 warriors were lured into a trap by Uncas, and in the battle of 1643 he was captured and then executed. The plaque states:

"For years, Narragansetts visiting the spot of Miantonomo's capture honored their sachem's memory by placing a small stone at this memorial site.

The resulting cairn was removed long ago to use the stones for local construction.

Dr. Noah Webster to Rev. Ezra Stiles [President of Yale College] Jany. 20th 1788

It is said by the English, who are best acquainted with the manners of the natives, that they had a custom of collecting, at certain stated periods, all the bones of their deceased friends and burying them in some common grave. Over these cemetaries or general repositories of the dead, were erected those vast heaps of earth or mounts similar to those which are called in England barrows, and which are discovered in every part of the United States. The indians seem to have had two methods of burying the deadone was, to deposit one body (or at most but a small number of bodies), in a place, and cover it with stones, thrown together in a careless manner. The pile thus formed would naturally be nearly circular, but those piles that are discovered, are sometimes oval. In the neighborhood of my fathers house, and about 7 miles from Hartford, on the public road to Farmington, there is one of these Carnedds [cairns] or heaps of stone. I often passed by it in the early part of my youth, but never measured its circumference or examined its contents. My present opinion is that its circumference is about 25 feet. The inhabitants in the neighborhood report, as a tradition recieved from the natives, that an Indian was buried there, and that it is the custom for every Indian that passes by, to cast a stone upon the heap. This custom I have never seen practised; but have no doubt of its existence, as it is confirmed by the general testimony of the first American settlers.

The other mode of burying the dead was to deposit a vast number of bodies, or the bones which were taken from the single scattered graves, in a common cemetary, and over them raise vast tumuli or barrows; such as the mount at Muskingum, [on the West Virginia, Ohio border] which is 390 feet in circumference, and 50 feet high. The best account of these cemetaries may be found in Mr. Jefferson s Notes on Virginia, which will appear the most satisfactory to the reader in his own words.

Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, 1787:

. . . Barrows, of which many are to be found all over this country. These are of different sizes, some of them constructed of earth, and some of loose stones. That they were repositories of the dead, has been obvious to all: but on what particular occasion constructed, was matter of doubt. Some have thought they covered the bones of those who have fallen in battles fought on the spot of interment. Some ascribed them to the custom, said to prevail among the Indians, of collecting, at certain periods, the bones of all their dead, wheresoever deposited at the time of death. Others again supposed them the general sepulchres for towns, conjectured to have been on or near these grounds; . . .

But on whatever occasion they may have been made, they are of considerable notoriety among the Indians: for a party passing, about thirty years ago, through the part of thecountry where this barrow is, went through the woods directly to it, without any instructions or enquiry, and having staid about it some time, with expressions which were construed to be those of sorrow, they returned to the high road, which they had left about half a dozen miles to pay this visit, and pursued their journey. There is another barrow, much resembling this in the low grounds of the South branch of Shenandoah, where it is crossed by the road leading from the Rock-fish gap to Staunton. Both of these have, within these dozen years, been cleared of their trees and put under cultivation, are much reduced in their height, and spread in width, by the plough, and will probably disappear in time. There is another on a hill in the Blue ridge of mountains, a few miles North of Wood's gap, which is made up of small stones thrown together. This has been opened and found to contain human bones, as the others do. There are also many others in other parts of the country.

Rev. Timothy Dwight (President of Yale College); Travels in New-England and New-York; 1821;

Vol. 2, p.380:

From Barrington, in our way to Stockbridge, we crossed Monument mountain: a spur from the Green Mountain range. The name is derived from a pile of stones, about six or eight feet in diameter, circular at its base, and raised in the form of an obtuse cone* over the grave of one of the aborigines. The manner, in which it has been formed, is the following- Every Indian, who passes by the place, throws a stone upon the tomb of his countryman. By this slow method of accumulation, the heap has risen in a long series of years to its present size. The same mode of raising monuments for the dead, except in one particular, has existed among other nations. . . . By the natives of America it seems to be an expression of peculiar reverence, and an act of obedience to the dictates of their religion. [* an 'obtuse cone' is one which does not reach a sharp point, but rather ends with a broad top.]

Vol 3, p. 109:

The country from Sandwich to Plymouth[, Massachusetts] is a continued forest with a few solitary settlements in its bosom. The surface is, principally, a plain; but at times swelling into hills. Wherever the road lies on the shore the prospects are romantic; but wild and solitary. The forest is, generally, composed of yellow pines; the soil is barren; and the road almost universally sandy; but less deep than that, which has been heretofore described. We passed several places, which, in this region have been kept in particular remembrance from an early period. Among them is a rock, called Sacrifice Rock; and a piece of water, named Clam-pudding Pond. On the former of these the Indians were accustomed to gather sticks, some of which we saw lying upon it, as a religious service, now inexplicable.

Vol. 3, p. 403:

After we had examined the falls of this river, and its passage through the mountains below, my companions ascended the summit of that on the Eastern side, for the purpose of seeing a monument of stones, formed in a manner generally resembling that which I have heretofore described in these letters, as existing on Monument mountain, near Stockbridge[, Massachusetts]. It was intended to mark the grave of an Indian chief, who was buried here. This chief was one of the Scaghticokes : a tribe which I have heretofore mentioned, and of which New-Milford was formerly the principal residence. His crime was the murder of one of his own people. In consequence of this act he was immediately pursued by the avenger of blood; who, among the Mohekaneews, and among the Iroquois also, was, usually, the nearest male kinsman. The chief fled to Roxbury; a township bordering on New Milford South-Eastward; thence to Woodbury; and thence to Southbury: in which township he came upon the river. He then directed his course up the stream, till he reached the summit of this mountain; where he was overtaken, and killed, by his pursuer, on the spot in which he was buried. The figure of this monument was, in one respect, different from that which is in the neighbourhood of Stockbridge. That was an obtuse cone. This is a circular enclosure, surrounding the grave. Both were, however, gathered in the same manner. Every Indian, at least of the tribe to which the deceased belonged, considered himself as under a sacred obligation, whenever he passed by, to add one stone to the heap; as did, I believe, those of every other tribe, belonging to the same nation. In this gradual manner both monuments were accumulated. It is remarkable, that both are on high, and solitary, grounds, remote from every Indian settlement; and that the persons buried were excluded from the customary burying places of their respective tribes; places considered, I believe, by all the Mohekaneews as consecrated ground. Of both it is also true, that the Indians have declared the obligation to cast any more stones upon them to have ceased for a considerable period. Of the chief, buried here, it is certain, that he was considered as having committed a gross crime. . . . Within a short time past, some young gentlemen, studying physic in the neighbourhood, attempted to dig up the bones of this deceased chief. The attempt, while it destroyed an interesting relic of Indian manners, gave very great offence to the Schaghticokes; who threatened them with violence for the injury done to their tribe.

Vol. 3 p.408:

On our way to Stockbridge[, Massachusetts] we went to the Indian monument, mentioned in a former part of these letters; and, to our great regret, found it broken up in the same manner, as that at New-Milford. I ought, in my account of that, to have added, that this mode of erecting monuments was adopted only on peculiar occasions. The common manner of Indian burial had nothing in it of this nature. The remains of the dead, who died at home, were lodged in a common cemetery, belonging to the village, in which they had lived. Sometimes they were laid horizontally, and sometimes were interred in a sitting posture. . . . These, monuments were plainly erected under the sanctions of Religion : for every Indian felt himself religiously obliged, when he passed by, to cast a stone upon them. How long this obligation extended is to me unknown; but it had its termination : for the Indians, in both these instances, consider themselves as having been released from it a good number of years. Both of them were also raised upon extraordinary occasions. What those occasions were it may now be impossible to determine.

Through the 18th and well into the 19th

Centuries, it was well-known that many cairns were erected in

conjunction with burials and that Natives would go out of their way to

visit them to pay their respects to the deceased. Washington

Irving was yet another chronicler of this tradition. The

Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon; 1819:

"Tribes that have passed generations exiled from the abodes of their

ancestors, when by chance they have been travelling in the vicinity,

have been known to turn aside from the highway, and, guided by

wonderfully accurate tradition, have crossed the country for miles to

some tumulus, buried perhaps in woods, where the bones of their tribe

were anciently deposited, and there have passed hours in silent

meditation."

E. G. Squier, Antiquities of the State of New York, Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, Vol. II, 1851; p. 164-5:

". . . occasional large heaps of stone, the work of the aborigines, are to be found in the State of New York. Particular reference was made to one in Scoharie county, which is described more in detail in Howe's Gazetteer of New York, as follows:

Between Scoharie creek and Caughnawaga was an Indian trail, and near it, in the north bounds of Scoharie county, has been seen, from time immemorial, a large pile of stones, which has given the name of "stone heap patent" to the tract on which it occurs, as may be seen from ancient deeds. Indian tradition says that a Mohawk murdered his brother on this spot, and that this heap was erected to commemorate the event. Every individual who passed that way added a stone to the pile, in propitiation of the spirit of the victim.'

A letter from Rev. Gideon Hawley of Marshpee containing a Narrative of his Journey to Onohoghgwage in 1753 [from Doc. Hist. of NY vol III p. 1039, from 1 Mass. Coll. IV]:

"Mr. Butler obtained for us an Indian guide to conduct us across to Schoharry, about sixteen miles south, through a wilderness. . . . We came to a resting place, and breathed our horses, and slaked our thirst at the stream, when we perceived our Indian looking for a stone, which having found, he cast to a heap, which for ages had been accumulating by passengers like him, who was our guide. We inquired why he observed that rite. His answer was, that his father practiced it, and enjoined it on him. But he did not talk on the subject. I have observed in every part of the country, and among every tribe of Indians, and among those where I now am, in a particular manner, such heaps of stones or sticks collected on the like occasion as the above. The largest heap I ever observed, is that large collection of small stones on the mountain between Stockbridge and Great-Barrington [Massachusetts]. We have a sacrifice rock, as it is termed, between Plymouth and Sandwich, to which stones and sticks are always cast by Indians who pass it. This custom or right is an acknowledgment of an invisible being. We may style him the unknown God, whom this people worship. This heap is his altar. The stone that is collected is the oblation of the traveler, which, if offered with a good mind, may be as acceptable as a consecrated animal."

Barber, J. & Howe, H.; Historical Collections of the State of New York Containing a General Collection of the Most Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes; 1841:

"Somewhere between Schoharie creek and Caughnawaga commenced an Indian road or foot path, which led to Schoharie. Near this road, and within the Northern bounds of Schoharie county, has been seen from time immemorial a large pile of stones, which has given the name Stone heap patent' to the tract on which it occurs, as may be seen from ancient deeds."

Hopkins, Samuel, Historical memoirs, relating to the Housatunnuk Indians: or, An account of the methods used, and pains taken, for the propagation of the gospel among that heathenish- tribe . . , 1753; p.11:

"There is a large heap of stones, I suppose ten cart-loads, in the way to Wanhktukook, which the Indians have thrown together as they passed by the place: for it used to be their custom, every time one passed by, to throw a stone upon it: but what was the end thereof they cannot tell, only that their fathers used to do it, and they do it because it was the custom of their fathers."

Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 71; The Smithsonian Institution; Native Cemeteries and Forms of Burial East of the Mississippi; David Bushnell; 1920; p. 17:

"As early as 1720 some English traders saw a large heap of stones on the east side of the Westenhook or Housatonic Rover, so called, on the southerly end of the mountain called Monument Mountain, between Stockbridge and Great Barrington.' This circumstance gave rise to the name which has ever since been applied to the mountain, a prominent landmark in the valley. This ancient pile of stones may have marked the grave of some great man who lived and died before the coming of the colonists."

Northeast

Southeast

Mississippian

West

Pennsylvania- Stylized cairns and walls

Vermont- Platform cairns

Wisconsin- Astronomically aligned cairns

Georgia- Investigations of Two Stone Mound Localities, Monroe County (6.2 MB PDF)

Georgia- Rock Eagle effigy cairn of quartzite listed on the National Register in 1978

Georgia- Rock Hawk effigy cairn surrounded by a stone circle

W. Virginia-

Smithsonian documentation of Native

cairns

Indiana- "a low dome-shaped [cairn] measuring about 55 by 50 feet and 4 feet high"

Montana- Cairns used to drive big game over precipices

Ohio- Photo (lower left) of a stone mound

Ohio-

Stone altar incorporated into

Alligator Mound and

![]()

Minnesota- Cairn "twelve feet in diameter and six in height"

California- Federal Register documentation of cairn burials

Alabama- bibliography of stone mounds

Indiana- Stone mounds on the Whitewater

Georgia- Stone mound 10 meters long by 5 meters wide and 1-1/2 meters high

Upper Peninsula of Michigan- stone cairns photos (scroll to bottom of page)

Rockies- Cairns along the Lewis & Clark route

Georgia - Three great cairns of white stone, surrounded by many small rock cairns.

Massachusetts- The location of the Sacrifice Rock on the road between Sandwich and Plymouth

![]()

© Copyright 2004-2005, NativeStones.com. All rights reserved. All original materials on this site are protected by United States copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed or published without prior written permission. You may not alter or remove any copyright notice from copies of the content. You may download material from this site only for your personal, noncommercial use.

© Copyright 2004-2005, NativeStones.com. All rights reserved. All original materials on this site are protected by United States copyright law and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed or published without prior written permission. You may not alter or remove any copyright notice from copies of the content. You may download material from this site only for your personal, noncommercial use.