|

Stone chambers: Native

temples

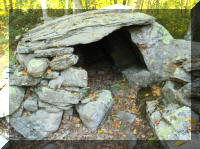

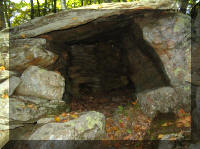

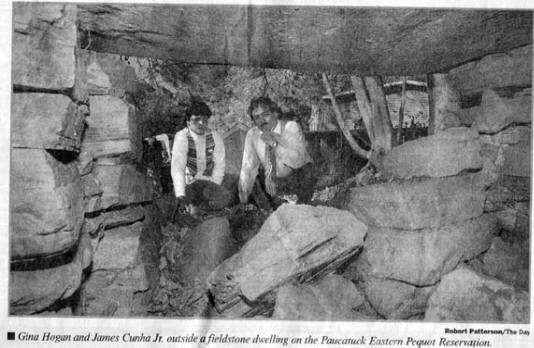

A stone chamber is defined as a Native temple

covered with a stone slab roof, in which the stones were

quarried without the use of metal drills. There are around

500 of these structures extant in the Northeast. Their

distribution is largely confined to southern New England and the

southeastern portion of New York state. To the north,

chambers occur into central Vermont and New Hampshire.

There is perhaps one example in

the state of Maine. They extend into Westchester County in

southeastern New

York. There are rumors of several examples west of

the Hudson River and into eastern Pennsylvania, but with a few scattered exceptions, these are

unconfirmed. The densest concentration is found in Putnam

County, NY, on the east bank of the Hudson, just north of

Westchester, where around 200 examples occur within that county

or immediately outside its borders. The second-densest

concentration occurs in New London County in southeastern

Connecticut, with probably around 50 extant chambers.

Windsor

County in central Vermont probably has somewhat less than New

London County. Together, these three counties account for

the majority of stone chambers in America. These are not

designed as root cellars, which are found in the cellars of Colonial homes.

Some chambers are entirely or partially out of the ground,

precluding their use for food storage. These range from tiny

examples of perhaps a foot or two of cubic volume on up to

massive structures of over 300 square feet in floor plan. There

are many more Native foundations which were never roofed with

stone slabs, and which apparently were covered with timber.

Both the chambers and foundations serve as entrances into the

Earth Mother, and frequently are designed to be illuminated by

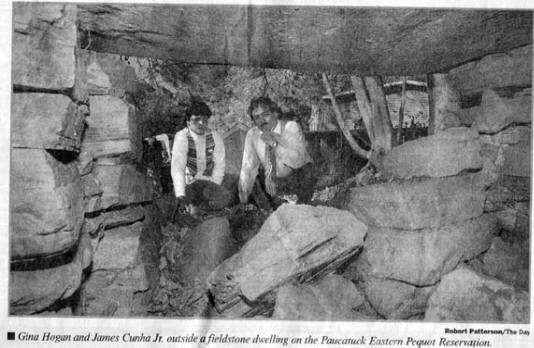

the sun or moon on key calendrical events. The example

illustrated below is on the Eastern Pequot reservation in

Ledyard, CT, land never owned by Whites.

Early references to stone chambers (called "stone

houses" or "stone forts") are reproduced below:

Notes to Wawekas Hill, or Mohegan's

Watchtower and Tombstone, c. 1769, apparently written by Mr.

Hide of Norwich, as reproduced in Bulletin 34, Archaeological

Society of Connecticut, 1966, p. 41-44:

"Aged people whose fathers remembered the days of Uncas, . . .

uniformly called [Wawekas H]ill by the name of the Indian Watch

Tower. . . . The Fort upon this Hill was a large square

building erected in the Indian manner of unpolished stone,

without mortar, embanked with earth. The remains of this

structure have been visible until within a few years. It

probably stood in good repair in the days of Uncas; and though

more than one hundred thirty years have passed since that time,

but for the depredations of those who wished to enclose their

farms with stone fences, it might have stood firmly at the

present day."

F. M. Caulkins, History of Norwich, 1866; p. 23:

"Waweekus Hill . . . [the] ancient name of Fort Hill." [Miss

Caulkins provides the original name of what had by then become

known as simply "Fort Hill."]

Robert Boucher, unpublished MSS c.1990 on the earliest deeds

of New London, CT:

". . . the land records show the existence of Stone Houses'

or Indian Forts.' . . . They seem to have all been

built on a hill which invariably acquired the name of Fort

Hill.' . . . To date, the writer has isolated the location of

three of these Indian forts."

Boucher's footnotes list these as: 1) Laid

out to Richard Douglas - 4/11/1733; 2) William Hough to Richard

Blinman - 6/5/1656; 3) Samuel Rogers to James Rogers Sr. -

2/15/1669

Boucher's use of the word 'fort' echoes the term Pynchon

used in 1654 (reproduced on our

home page): "a

stonewall and strong fort ."A very

minor percentage of stone chambers are clearly not ancient.

This is sometimes revealed by their architecture (which differs

from the vast majority of chambers) and the presence of drill

holes in the stones which comprise the walls and roof of a

chamber. The presence of drill holes in a chamber does not

preclude the possibility of it being ancient. Many

chambers have been repaired since c. 1750, when drill marks

first begin to appear in the stone record in New England.

Such repaired chambers -- which were recycled for uses including root cellars, housing and

storage sheds -- often

reveal their antiquity by an absence of drill marks on the

lowest courses of stones. These lower courses are

generally the most stable and least subject to needing repair

from tree uprootings or other events which conspire to dismantle

chambers.

Root Cellars? Many have confused

Native stone chambers with Colonial or later root cellars. While

there are small numbers of detached root cellars, these are

normally easy to distinguish from ancient chambers because their

design is not typical of that displayed in chambers.

While it is understandable that a cursory examination of one or

several chambers could lead to a root cellar conclusion, this

does not bear up when the entire corpus of chambers is given

careful scrutiny. Such an examination reveals the

following:

-

The early accounts reproduced above make

clear that chambers were found by the first European

settlers.

-

The size of some chambers precludes a

food storage use. Some are as small as about one cubic

foot while others are as large as several hundred cubic feet.

Both make little sense in terms of storing crops.

>>More

-

The distribution of chambers makes no

sense agriculturally. Putnam County, NY (home to

around 40% of the extant chambers) is a region of miserable

terrain. For this reason it was the last portion of

the lower Hudson Valley to be settled. The first

settlers did not arrive until c. 1750. The county was

never an agricultural district because it was too hilly and

mountainous to produce many crops. Most agriculture

was confined to sheep and dairy farming. The

distribution of the chambers within the county is heavily

weighted toward the three towns within its center and which

possess the worst terrain within the county. If

chambers were designed to store agricultural produce, their

distribution should be uniform across not only New England,

but the rest of the Eastern states as well. They

should not be confined to areas where often the very

least amount of produce was grown.

-

Root cellars require ventilation and

insulation from temperature extremes. A small number

of chambers (consistent in design with the vast majority of

chambers) are built fully or partially out of the ground.

Almost all the chambers lack transverse ventilation, without

which produce will soon rot from molds and the buildup of

ethylene gas produced by the fruits and vegetables to hasten

their own ripening.

>>More

-

External root cellars must be sealed by a

door or a pair of doors to insulate the interior from

temperature extremes. Most chambers make no provision

in their design for the attachment of a door. Those

which have been recycled and today possess a door have had

door jambs inserted into their entrances. In many

cases, the entry into chambers is absurd it terms of both

sealing the opening and facilitating the transportation of

produce through the entrance. A doorway 99 inches high

in a large, formal chamber is far too high to easy seal.

On the other end of the height scale, some chambers require

entrants to crawl into them.

>>More

-

Mavor and Dix were the first to examine

the possibility that chambers are astronomically oriented.

Since then, it has become abundantly clear that many are.

One common design is a dark-half of the year chamber:

light from the rising sun will first penetrate to one corner

of the base of the rear wall on the autumnal equinox, touch

the opposite corner on the winter solstice, and then return

to the original corner on the vernal equinox.

-

Many chambers (along with U-shaped

constructions) will have an anchoring boulder on the right

side (when facing in) of the front entrance. It is not

known if there are any left-side anchoring boulders.

This is further evidence of chambers being ritualized,

sacred architecture.

It would be an omission to not mention the close correspondence

between chambers and U-shaped structures.

Both are different styles of the same thing: artificial,

ritualized entrances into the Earth Mother. Chambers

differ from the U-shaped constructions in possessing a stone slab roof and

are

generally more formal constructions evidencing greater

complexity and size. But this does not always hold true.

A comparison of numerous chambers and U-shaped constructions

reveals both to be separate aspects of the same basic design.

Foundations

Foundations are identical to many chambers

with one exception: a lack of a stone slab roof. This

allowed many foundations to be built to much greater dimensions

than could be easily spanned by a stone slab roof, although

very small foundations also occur. . . . . (to be

continued)

|