|

Did Old World

peoples create the antiquities of North America?

Although the answer to the

above question might seem self-evident, this has not always been the

case. While a reasonable person might describe the romantics

--who believed the antiquities of this hemisphere were largely created

by Old World visitors-- as simply silly (if not racist in that they

denied the Native inhabitants of North America the ability and

motivation to create monumental architecture), the truth is that huge

amounts of ink have been wasted attempting to prove the absurd.

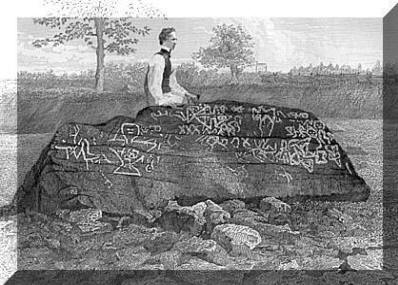

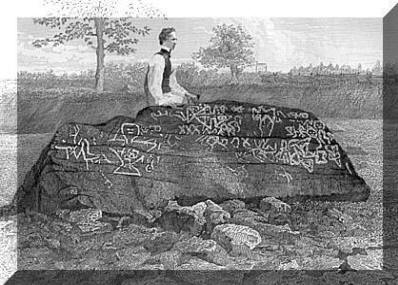

By 1789, for example,

speculation over the origin of the inscriptions on Dighton Rock

(shown below) on the Massachusetts coast had already been underway for

over a century. George Washington, as the anecdote below

relates, was one of the few still fluent in some of the Native ways:

Volume 10, Massachusetts Historical Society

Proceedings; 1868; p.114-116; a letter dated August 10, 1809 from John

Lathrop to Judge John Davis:

“Dear Sir,

--Agreeably to your request, I hasten to communicate the substance of a

conversation with the late President Washington, relating to the

inscription on a rock in Taunton river, which has been the subject of

interesting research, from the first settlement of Europeans in this

part of America.  The

learned have been divided in opinion respecting the origin of that

inscription: some suppose the origin to be Oriental, and some

Occidental. The

learned have been divided in opinion respecting the origin of that

inscription: some suppose the origin to be Oriental, and some

Occidental.

Many Gentlemen acquainted with the Oriental languages

have thought several of the characters in the inscription bear a great

resemblance to some characters in the Oriental languages, particularly

the Punic. From the valuable communication which was made by you,

at the last meeting of the Academy, I perceive you favour the opinion

that the inscription was made by the native Indians of our country.

Having produced several important authorities, you mention the opinion

of the late President Washington.

As I am the only surviving member of the Corporation

present at the time when the late President gave the opinion you

mention, I now state to you the conversation on that subject. When that

illustrious Man was on a visit to this part of the United States, in the

autumn of 1789, the then President and Fellows of Harvard College waited

on him with an address, and invited him to visit the University in

Cambridge. While in the Musaeum I observed he fixed his eye on the full

length copy of the inscription on a rock in Taunton river, taken by

James Withrop, Esqr, and is exhibited in the Musaeum for the inspection

of the curious. As I had the honour to be near the President at that

moment, I took the liberty to ask him whether he had met with any thing

of the kind; and I ventured to give the opinion which several learned

men had entertained with respect to the origin of the inscription. I

observed that several of the characters were thought very much to

resemble Oriental characters; and that as the Phenicians, ‘as early as

the days of Moses are said to have extended their navigation beyond the

Pillars of Hercules,’ it was thought that some of those early navigators

may have either been driven off the coast of Africa, and were not able

to return, or that they willingly adventured, until they reached this

continent; and thus it was found, ‘Thule was no longer the last of

lands,’ and thus ‘America was early known to the ancients.’

Some

Phenician vessels, I added, it was conjectured had passed the island now

called Rhode-Island, and proceeded up the river, now called Taunton

river, nearly to the head of navigation. While detained by winds, or

other causes, now unknown, the people, it has been conjectured, made the

inscription, now to be seen on the face of the rock, and which we may

suppose to be a record of their fortunes, or of their fate. Some

Phenician vessels, I added, it was conjectured had passed the island now

called Rhode-Island, and proceeded up the river, now called Taunton

river, nearly to the head of navigation. While detained by winds, or

other causes, now unknown, the people, it has been conjectured, made the

inscription, now to be seen on the face of the rock, and which we may

suppose to be a record of their fortunes, or of their fate.

After I had given the above account the President

smiled, and said he believed the learned Gentlemen whom I had mentioned

were mistaken: and added, that in the younger part of his life, his

business called him to be very much in the wilderness of Virginia, which

gave him an opportunity to become acquainted with many customs and

practices of the Indians. The Indians he said had a way of writing and

recording their transactions, either in war or hunting. When they wished

to make any such record, or leave an account of their exploits to any

who might come after them, they scraped off the outer back of a tree,

and with a vegetable ink, or a little paint which they carried with

them, on the smooth surface, they wrote, in a way that was generally

understood by the people of their respective tribes. As he had so often

examined the rude way of writing practised by the Indians of Virginia,

and observed many of the characters on the inscription then before him,

so nearly resembled the characters used by the Indians, he had no doubt

the inscription was made, long ago, by some natives of America.”

A few generations

later, Daniel Brinton, fully conversant with Native ways, was

typical of the serious researchers of his day who still

knew Dighton Rock's inscription was Native, a fact which has

since become more obscure with each passing decade:

The myths of the New world; a treatise on

the symbolism and mythology of the red race of America; Daniel Brinton;

1876

"This kind of writing, if it deserves

the name, was common throughout the continent, and many specimens of it,

scratched on the plane surfaces of stones, have been preserved to the

present day. Such is the once celebrated inscription on Dighton Rock,

Massachusetts . . ."

Dighton Rock is an example of

the sort of controversy which raged for decades over the question of who

built the 200,000 earthen mounds in the middle of the continent.

Not until the end of the 19th

Century, when the Smithsonian waded into the debate, did the

pendulum swing toward a Native explanation. The Smithsonian

research and publications made a strong case for Native construction of

the massive collection of earthworks in the Midwest, finally ending most

debate. Yet over a century later, there are still a few who cling

to the belief that a mysterious race of Moundbuilders once

inhabited this country.

While the question of who built

the antiquities is long settled in the Midwest, it is only beginning to

be addressed in the Northeast. The Northeast is today where the

Midwest was 150 years ago. People are only beginning to

recognize and catalogue the remaining Northeastern antiquities.

And in regions such as California, almost no one is focused on features

such as the Native stone walls, cairns or propped boulders which survive

there. The debate will only be settled when all these

constructions are examined together (not as individual specimens)

and in the wider context of Native American stonework found across the

entire continent.

Reawakened awareness of New

England stone antiquites

While it is clear from early accounts of such

things as stone

cairns,

walls

and

chambers, that there

had once been widespread recognition in New England of the existence of

Native American stonework, by the 20th Century few were still

familiar with this literature. William Goodwin's 1946 The Ruins

of Great Ireland in New England marked the beginning of the modern

effort to document and understand these constructions. Goodwin and

his cohorts began to locate stone chambers and complexes such as

Mystery Hill.

Goodwin eventually purchased Mystery Hill and began the investigation

and restoration of this important site. Organizations such as the

Early Sites Research Society (disbanded c. 2000), the

New

England Antiquities Research Association (founded 1964) and

the

Gungywamp Society

in Connecticut (founded 1979) were established in response to the

growing realization of the widespread distribution of such antiquities.

Goodwin concocted a grand theory of Irish

Culdee monks who visited New England in the 10th Century

and left behind the many stone chambers he and his associates were

stumbling across. The absence of comparable stone constructions in

Ireland should serve as a warning against investing any credibility in

the many other wild speculations incorporated into his book.

Goodwin's opinion on the Algonquian Natives of this region are best

stated in his own words: ". . . we utterly fail to see any

improvement or even change in their manners, minds, customs or actions,

subsequent to the attempt to Christianize them." Given this

mindset, there was little chance Goodwin would ascribe these works to

Native authors. Rather, his absurd conclusion that they were the

work of people who did not build such structures in their homeland

struck a chord in the public's imagination. Unfortunately, this

nonsense still echoes down to the current era. It is almost

impossible to read Goodwin. There is little internal organization

of his 424-page book and what he attempts to pass off as logic, isn't.

For example, on the second page of his first chapter, Goodwin spells out

the twisted method of arriving at his primary conclusion:

"One of

the first steps taken by this author was to obtain books from London and

Dublin covering the question as to whether any type of stone work was

Norse. In the final analysis we became convinced that these

curious buildings were of a type found in Ireland, the British Isles and

on Continental Europe where they are considered to have been the work of

an early people, and had no Norse background whatsoever. In the

end, we reduced this to Cornwall, Spain, Ireland and Scotland and became

of the opinion that all the sites whenever located in Maine, New

Hampshire and Massachusetts were the work of Irish Culdee monks and

their families with the aid of Indian converts."

Uh huh. It is extraordinarily difficult to read

Goodwin. Neither his logic nor his writing is easy to follow.

It is hard to believe he wrote in the middle of the 20th

Century. His writing would have made for bad speculation in the 18th

Century, except for the fact that this would have been impossible

because knowledge that these sorts of stone constructions were Native

was still too widespread at that date. Precisely at the same time

he wrote, intelligent researchers were busy studying the Native

stonework in New England. During the first part of the 20th

Century, Frank Speck from the University of Pennsylvania was the

preeminent researcher of Native American anthropology in the Northeast.

He had noted the enduring practice of Lenapes (in the mid-Atlantic

region) of building stone and brush memorial heaps into the early

20th Century. In 1946, the same year Goodwin published,

Eva Butler of Connecticut followed up on Speck's work and published an

important review article in that state's archaeological society's

bulletin of the same practices in Southern New England. Butler

followed Speck in being one of the leading New England researchers of

Native American subjects in the middle of the last century. A

decade later, Frank Glynn, president of Connecticut's archaeological

society, excavated a pair of stone cairns on that state's coast,

revealing them to be clearly Native in origin. His work was done

in close collaboration with Prof. Irving Rouse of Yale, founder of that

society. The report of Glynn's excavations was finally published

posthumously by the Connecticut Archaeological Society in 1973.

Glynn stated: "This excavation had its inception in a conversation

with Dr. Irving Rouse and Mr. Lyent Russell in the winter of 1952.

Under discussion was a prevalent archaeological belief that there are no

prehistoric mounds or structures in New England. Rouse and Russell

suggested that the well-documented ([Eva] Butler, 1946)

Connecticut stone heaps offered an opportunity for testing the

generalization."

Goodwin's title encapsulates the early thinking (over

the course of several decades in the mid-20th Century) about

the origin of the builders of these stone constructions. Without a

thorough grasp of three areas, it was easy to fall into this logical

trap. The six decades since Goodwin have brought a much greater

understanding of these three subjects: 1) the

stonework of Ireland and

the rest of western Europe, 2) the stonework of the Northeast and 3) the

stonework context of the rest of North America. The past couple of

decades have also witnessed a growing understanding of Native American

cosmology and the sacred architecture which memorializes these concepts.

Both in North and South America, using anthropological and

archaeological methods, a remarkable amount of the past has been brought

back to life. While regional differences abound in the New World,

the extant sacred architecture clearly reveals an underlying cosmology

focused on the Mother Earth/Father Sky duality and an effort to unite

these two entities, as well as a focus on the sprit world which suffuses

both. In the intervening decades, Goodwin's Mystery Hill has been

subject to intense scrutiny and mapping. This has revealed a

massive solar calendrical device incorporated into the architecture of

the site. The features found at Mystery Hill are all found in less

dense contexts elsewhere throughout the Northeast. But they are

not found in the context of Culdee monks in the Old World. Nor are

the European structures Goodwin latched onto the product of Culdee

monks.

From our current vantage point, it is clear that,

just as the Mississippian and Anasazi sacred architecture are the

remains of two vanished, distinct civilizations, the Northeastern

stonework is the unique product of an indigenous, Native civilization.

While related (in both design and cosmological configuration) to stone

(and earthen) constructions found elsewhere in the New World, the

Northeastern architecture is a distinct style found nowhere else in

the world. While similar individual examples of things

such as

cairns,

walls,

petroforms or

propped boulders are

located elsewhere in North America, nowhere else do these sorts of

constructions appear in the same complex configurations and density as

they do in the Northeast. Too long a subject to explore here, the

Native stonework of the Northeast reveals a thorough understanding of

three facets of a comprehensive cosmology: 1) the landscape features of

the the Earth, 2) the cycles of the Sky and 3) the geology underlying

the landscape, at the entrance to the Underworld were so much of the

spirit world takes place. The sacred architecture served to unite

these concepts.

Was Fell

even partly right?

Getting back to Fell,

there were two primary components in his work: an expansion upon

Goodwin's Irish Culdee monk speculations and a focus on the ancient

inscriptions of America. He would have been better off to have

simply skipped the former and focused on the latter. What set Fell

apart was that he was the first to fully recognize the widespread

existence in the New World of stone inscriptions in scripts which are

also found in the

Old World. Fell erred in immediately presuming an Old World

origin for the drafters of these New World inscriptions.

Take ogam

(a.k.a. ogham) script, for example. At the time when

Fell wrote of discovering many ogam inscriptions in the U.S., it was

generally assumed that ogam was a European script, as it was last used

in Ireland in the medieval era. Since then, it has been learned

that ancient ogam inscriptions are found on every continent, with North

America hosting the largest collection. Today, no one has any idea

where ogam may have originated. All we know for sure is that it

was in widespread use across the globe.

Fell's error was to confuse

a script with a race. The absurdity of this reasoning is

revealed when one considers English, originally an obscure

northern European dialect only a millennium ago. The page

you are reading is written in a Latin script, using Arabic

(originally

Hindu) numerals, and is in a language widely spoken and written

in every corner of the planet by individuals of every race.

English text today serves as the modern version of ogam: a script in

worldwide use allowing disparte peoples to communicate.

One of Fell's primary

contributions was to focus attention on the Northeastern stone

antiquities, a subject only beginning to attract investigation in 1976.

He recognized the likely antiquity of these constructions, but erred in

determining their builders. Fell was also correct in recognizing

the likelihood of a massive amount of communication between the Old and

New Worlds in antiquity. This is the central contention of the

paradigm of

diffusionism to explain why similar things are found in distant

regions of the world, as opposed to the concept of independent

invention. Diffusionism, for example, attempts to understand

why pyramids are found in the

Middle East, Canary Islands and Mexico.

This is a vast subject in much dispute, falling outside the bounds of

this discussion. Just two examples suffice to underscore the solid

foundation of this concept:

1) Roger Williams,

founder of Rhode Island, noted in the early 17th Century that

the Native inhabitants of that region referred to the Big Dipper

and Little Dipper

constellations as the Great Bear and Little Bear,

alternate names used in Europe as well (familiar to us as the

Latin Ursa Major and Ursa Minor):

Key into the

Language of the Indians of New England,

1643: "By occasion of their frequent lying in the fields or

woods, they much observe the stars; and their very children can give

names to many of them, and observe their motions; . . . Mosk or

Paukunnawaw [is the name of]; the Great Bear, or Charles' Wain [Big

Dipper], which words Mosk, or Paukunnawaw signify a bear; which is so

much the more observable, because in most languages, that sign or

constellation is called the Bear."

2) William Sullivan, in 1997 in

The Secret of the Incas, threw down the gauntlet to the

isolationists who would have us believe Columbus was the first to make

the voyage between hemispheres:

"If contact between Old World and New is

unacceptable as an explanation for why, in the Andes, the planet Saturn

was conceived of as the ancient mill bearer, Jupiter as the king who

hurls, Venus as a beautiful woman with curly hair, and Mars as the ruler

over warfare, then the time has come for those who reject this

explanation to step up and provide a plausible alternative. . . .

we are leaving nothing less than a history of the human race,

unsuspected and unimagined, to gather dust on dark shelves."

Planets and constellations were

known by the same terms on both sides of the Atlantic. The odds of

this being explainable by mere coincidence converge toward zero.

The ever-cogent Thomas

Jefferson will have the final word on this subject [from

Notes on the State of Virginia; 1781]:

"Great question has arisen from whence came those aboriginal

inhabitants of America? Discoveries, long ago made, were sufficient

to shew that a passage from Europe to America was always

practicable, even to the imperfect navigation of ancient times. In

going from Norway to Iceland, from Iceland to Groenland, from

Groenland to Labrador, the first traject is the widest: and this

having been practised from the earliest times of which we have any

account of that part of the earth, it is not difficult to suppose

that the subsequent trajects may have been sometimes passed. Again,

the late discoveries of Captain Cook, coasting from Kamschatka to

California, have proved that, if the two continents of Asia and

America be separated at all, it is only by a narrow streight. So

that from this side also, inhabitants may have passed into America:

and the resemblance between the Indians of America and the Eastern

inhabitants of Asia, would induce us to conjecture, that the former

are the descendants of the latter, or the latter of the former:

excepting indeed the Eskimaux, who, from the same circumstance of

resemblance, and from identity of language, must be derived from the

Groenlanders, and these probably from some of the northern parts of

the old continent. A knowledge of their several languages would be

the most certain evidence of their derivation which could be

produced.

In fact, it is the best proof of the affinity of nations which ever

can be referred to. How many ages have elapsed since the English,

the Dutch, the

Germans,

the Swiss, the Norwegians, Danes and Swedes have separated from

their common stock? Yet how many more must elapse before the proofs

of their common origin, which exist in their several languages, will

disappear? It is to be lamented then, very much to be lamented, that

we have suffered so many of the Indian tribes already to extinguish,

without our having previously collected and deposited in the records

of literature, the general rudiments at least of the languages they

spoke. Were vocabularies formed of all the languages spoken in North

and South America, preserving their appellations of the most common

objects in nature, of those which must be present to every nation

barbarous or civilised, with the inflections of their nouns and

verbs, their principles of regimen and concord, and these deposited

in all the public libraries, it would furnish opportunities to those

skilled in the languages of the old world to compare them with

these, now, or at any future time, and hence to construct the best

evidence of the derivation of this part of the human race. Germans,

the Swiss, the Norwegians, Danes and Swedes have separated from

their common stock? Yet how many more must elapse before the proofs

of their common origin, which exist in their several languages, will

disappear? It is to be lamented then, very much to be lamented, that

we have suffered so many of the Indian tribes already to extinguish,

without our having previously collected and deposited in the records

of literature, the general rudiments at least of the languages they

spoke. Were vocabularies formed of all the languages spoken in North

and South America, preserving their appellations of the most common

objects in nature, of those which must be present to every nation

barbarous or civilised, with the inflections of their nouns and

verbs, their principles of regimen and concord, and these deposited

in all the public libraries, it would furnish opportunities to those

skilled in the languages of the old world to compare them with

these, now, or at any future time, and hence to construct the best

evidence of the derivation of this part of the human race.

But imperfect as is our knowledge of the tongues spoken in America,

it suffices to discover the following remarkable fact. Arranging

them under the radical ones to which they may be palpably traced,

and doing the same by those of the red men of Asia, there will be

found probably twenty in America, for one in Asia, of those radical

languages, so called because, if they were ever the same, they have

lost all resemblance to one another. A separation into dialects may

be the work of a few ages only, but for two dialects to recede from

one another till they have lost all vestiges of their common origin,

must require an immense course of time; perhaps not less than many

people give to the age of the earth. A greater number of those

radical changes of language having taken place among the red men of

America, proves them of greater antiquity than those of Asia."

HOME

©

Copyright 2004-2005,

NativeStones.com.

All rights reserved. All original materials on this site are

protected by United States copyright law and may not be

reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed or published

without prior written permission. You may not alter or remove

any copyright notice from copies of the content. You may

download material from this site only for your personal,

noncommercial use. |

![]()

![]()

The

learned have been divided in opinion respecting the origin of that

inscription: some suppose the origin to be Oriental, and some

Occidental.

The

learned have been divided in opinion respecting the origin of that

inscription: some suppose the origin to be Oriental, and some

Occidental. Some

Phenician vessels, I added, it was conjectured had passed the island now

called Rhode-Island, and proceeded up the river, now called Taunton

river, nearly to the head of navigation. While detained by winds, or

other causes, now unknown, the people, it has been conjectured, made the

inscription, now to be seen on the face of the rock, and which we may

suppose to be a record of their fortunes, or of their fate.

Some

Phenician vessels, I added, it was conjectured had passed the island now

called Rhode-Island, and proceeded up the river, now called Taunton

river, nearly to the head of navigation. While detained by winds, or

other causes, now unknown, the people, it has been conjectured, made the

inscription, now to be seen on the face of the rock, and which we may

suppose to be a record of their fortunes, or of their fate. Germans,

the Swiss, the Norwegians, Danes and Swedes have separated from

their common stock? Yet how many more must elapse before the proofs

of their common origin, which exist in their several languages, will

disappear? It is to be lamented then, very much to be lamented, that

we have suffered so many of the Indian tribes already to extinguish,

without our having previously collected and deposited in the records

of literature, the general rudiments at least of the languages they

spoke. Were vocabularies formed of all the languages spoken in North

and South America, preserving their appellations of the most common

objects in nature, of those which must be present to every nation

barbarous or civilised, with the inflections of their nouns and

verbs, their principles of regimen and concord, and these deposited

in all the public libraries, it would furnish opportunities to those

skilled in the languages of the old world to compare them with

these, now, or at any future time, and hence to construct the best

evidence of the derivation of this part of the human race.

Germans,

the Swiss, the Norwegians, Danes and Swedes have separated from

their common stock? Yet how many more must elapse before the proofs

of their common origin, which exist in their several languages, will

disappear? It is to be lamented then, very much to be lamented, that

we have suffered so many of the Indian tribes already to extinguish,

without our having previously collected and deposited in the records

of literature, the general rudiments at least of the languages they

spoke. Were vocabularies formed of all the languages spoken in North

and South America, preserving their appellations of the most common

objects in nature, of those which must be present to every nation

barbarous or civilised, with the inflections of their nouns and

verbs, their principles of regimen and concord, and these deposited

in all the public libraries, it would furnish opportunities to those

skilled in the languages of the old world to compare them with

these, now, or at any future time, and hence to construct the best

evidence of the derivation of this part of the human race.